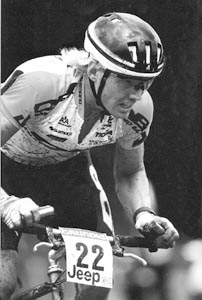

Dave Wiens

Profile: DAVE WIENS Finding the Perfect Formula

By Molly Murfee

This Article appeared in the Crested Butte Weekly June 25th, 2009

~MBHOF editor’s note: Many things have changed in our sport since this was written, but we have kept this story intact for posterity. August 26, 2015

When Dave Wiens itemizes his mountain biking rap sheet, it’s easy to see, even in this simple task, why he wins a lot. He is pointed and driven. He begins at the beginning, never falters, never errs from the path. He looks straight ahead, and one by one, just like cranks on the pedals, moves forward through his list of accomplishments. They range from two World Cup championships to beating one of the most famous bikers of modern times, Lance Armstrong, in the Leadville 100 of 2008.

For Dave, however, biking all began as transportation. With “itchy feet” to go places, steeped in a deep desire for independence, Dave needed a means to negotiate his childhood stomping grounds of Denver. Biking to places that were too far on foot gave him the autonomy he sought, and he began working in bike shops in Denver at age 15 when the sport was on the cusp of taking off. But it wasn’t there yet.

So in the summer of 1986, working in Denali as a raft guide, Dave surmises he must have been one of the first to mountain bike in Denali National Park in Alaska, armed with a bell on his bike to alert grizzlies of his presence. He rode in jeans. That summer he entered two mountain bike races in Anchorage and the seed was planted. The intensity of head to head racing, coupled with the physical demands, struck something in Dave’s mind.

When he had attended Western State College in the early and mid 80s, Dave tried his hand at alpine ski racing, but it just didn’t seem to be his sport. While living in Jackson Hole, Wyoming he experimented with extreme skiing.

“Super dangerous,” he says wide-eyed.

He tried kayaking, “hair boating” heinously tight waterways.

“This is really dangerous,” he notes as if just discovered, and is passing along important information.

And the mountain bike?

“It’s got brakes!”

Problem solved. Dave played his chips for mountain biking, becoming part of the local Tune Up Diamondback Team in 1988 after he returned to Gunnison for the final time, and thus “turned pro.”

“I just checked the box,” he laughs modestly, “It didn’t mean anything.”

Cutting his teeth on the local Rage in the Sage, he found himself competing against the top riders of the late eighties – John Tomac, Ned Overend, Mike Kloser and Rishi Grewal. Fortuitously timed, the sport also began picking up momentum. Dave was racing not only in his home state of Colorado, but traveling to other mountain biking meccas from California to Europe. The race circuit rocketed him into China, Japan, Australia, New Zealand and Canada. In 1996 he helped develop a course for the Olympics in Atlanta, then worked the races. The peak, however, was watching his fiancée at the time (now his wife), Susan DeMattei win the bronze medal in mountain biking.

For himself, Dave holds two World Cup race wins. “Two and a half hours,” he explains, “Not too long but highly intense.” Two National Championships. He’s won the Crested Butte Stage Race and Rage in the Sage. His win on the Kokopeli Trail Race was one of his favorites – beginning at midnight on a self supported fast trip to Moab.

“Two hundred and fifty ounces of liquids,” he shakes his head, “Fifteen pounds of liquid. The entire pack weighed about 25 pounds. It was a ridiculous pack. Luckily, it got lighter as I drank!”

He’s won the 100-mile Crested Butte Classic, the Inaugural Vapor Trail Race 125 out of Salida and 6 NORBA Nationals and two solid fistfuls of local races.

In 2003 he entered his first Leadville 100, a punishing 100-mile race to a high point of 12,600 feet. Although he had never raced that distance before – a 70-mile race in Europe was the closest he had come – he won it. Then he won it again. Then again. Six times in a row, the last time beating out Lance Armstrong.

“It’s crazy to think that the pressure I had for that one race, he has for 28 days,” says Dave of his Tour de France famed opponent in his most recent Leadville 100 Race, “It’s amazing he can deal with that kind of pressure. I just have a teeny tiny race – no one really even knows it outside of Colorado. But he’s worn that yellow jersey a lot in the seven years he did it. I have a ton of admiration and respect for how strong the guy is mentally. Unreal.”

Dave has also dabbled in adventure racing, using a map and compass to find his route.

“But it wasn’t my favorite,” he states matter-of-factly, “with a family it required too much time. If I was younger it might be better – not as many family obligations. “ says Dave. I’ve enjoyed exploring places on my bike, including here. When I first got here I was trying to find trails, exploring this country on my mountain bike, most of it alone. That’s what I’ve enjoyed the most in my career. It’s the best way to see the world.”

Traveling aside, staying in shape is the main reason Dave races. Having a goal keeps him in peak condition.

“A race isn’t mental to me,” he says steel-faced, “If my body is working well I can’t imagine I’ll have a mental breakdown. It’s power, recovery and endurance.”

“Staying in shape in a place like Gunnison County is easy, however. The valley attracts people who love to train. People migrate here for the outdoor training opportunities, not to train on an indoor trainer,” he pokes, “You have to be a little tougher here. We don’t have the training amenities. The place attracts tough people, so there are tough local competitors. We feed off of each other. When your next door neighbor is breaking records you think, ‘wow, if she can do it, I can too.’”

It is therefore also the challenge that lures Dave into racing. To him racing is black and white. Whoever crosses the finish line first – wins. It is a process – of training and being the most fit you can be. It is prepping your bike, creating tactics, setting a goal and achieving it.

“To win is just the cherry on top,” he elucidates, “You develop all of these different plans of various durations that emphasize the key elements of success, and then you plug away at executing them. It is not the glory of victory – it is the pure fun and motivation of the processes. The biggest, most general, plan is the several months leading up to the race. It’s important that I’m in pretty good shape in early July so I can begin a much more specific training plan that is aimed at being as good as I can be on that one day in August. Then it’s the bike prep, having the best ride possible for the race; the final nutrition: not too many cookies in the couple of weeks before the race; the details surrounding the race: how and where Susan will get me my feeds; what to have in the feed bag; the right food in the fridge for the final 2 or 3 meals before the race; all of the details that may come into play on race day. Once I’m actually in the race, that strategy is usually the easiest one to pull off. Plus, I’m also as relaxed as I’ve been in weeks, which seems kind of strange but it’s true. It’s more than being fit and having a good bike. It’s like a bunch of chaotic elements that finally all come together for that one day, that one purpose. I’ve been lucky that everything has worked out well for me to this point.”

Dave’s Original MBHOF Bio:

Wiens grew up in suburban Denver, and enjoyed skiing, fishing and camping with his family. He rode stingrays made into BMX bikes on the local trails (in vacant lots) and later rode a sweet candy apple red Schwinn Varsity on the trails as well as all over Denver for personal transportation. “Until I got my drivers license, my bike was my freedom,” he remembers. One time he wanted to go golfing but had no ride to the course. No problem though, he simply tied his dad’s pull cart to his seatpost with twine and headed for the course. Unfortunately, the knot came undone as he was going down a hill and the cart and clubs passed him on the right before piling into the curb. Luckily his father didn’t golf much and never noticed that the cart, the bag and some of the clubs got a little tweaked.

Dave’s actual mountain biking involvement started in the summer of ’82 while working in a bike shop in Denver. He ordered a beach cruiser and tried to make it into a MTB. Unlike the guys in Marin, he didn’t have the technology, but the bike worked okay on the Cherry Creek State Park nature trails (now closed to bikes.) Later that summer he mounted steel paper boy baskets to the bike, loaded them up with camping gear and headed up Fish Creek trail above Steamboat Springs. Let’s just say he picked the wrong trail, brought too much stuff, and his bike was a pile.

Dave’s first quality mountain biking came during the summer of 1986 while he was working in Alaska as a river guide in Denali National Park. His first real mountain bike was a ’95 Stumpjumper that was way too big (of course he didn’t know the difference). He rode all the trails around McKinley Village (now closed to bikes) wearing Levis and a flannel shirt with a copper bell on the bike which rang incessantly to hopefully ward off grizzly bears. That summer he entered his first races and has been hooked ever since. Today, that Stumpy is Dave’s townie.

Mountain biking has been the guiding compass for Dave’s life since 1987. For nearly fifteen years, it has been his passion and livelihood. Many of his friends are in the mountain biking community and it was while riding for the Diamond Back team that he met his lovely wife, Susan DeMattei. Dave’s favorite places to ride can be found on the vast public lands surrounding his home in the spectacular Gunnison Country in Colorado. In addition to pounding his way around race courses, Wiens has made and continues to make other contributions to the sport: He takes an active role in trail maintenance and enhancement of the Hartman’s Rocks trail system, the closest riding to his home in Gunnison. He is a positive role model for young racers and an inspiration to riders who, like him, are bigger and heavier than most of their competition (just a few more cookies and Wiens is racing in the Clydesdale class). He has been involved in the political processes of USA Cycling and NORBA, and served on both of these boards from 1995 through the year 2000. Dave helped design the Olympic Mountain bike course in Atlanta where his wife won the bronze medal in 1996. In 1998 he was awarded the Richard Long Sportsmanship award. Dave is still actively racing.

Beating Lance Armstrong, Then Getting Back to Life

By SEAN D. HAMILL

New York Times Article 10-14-08

GUNNISON, Colo. — This is the man who made Lance Armstrong cry “uncle.”

On a recent weekday morning here 7,700 feet up in the Rocky Mountains, with his wife already at work, David Wiens fed and packed up his three sons and cajoled them to get out the door to school, prepared for some volunteer work and hoped to maybe squeeze in an hourlong bike ride before rushing off to pick up the children in the afternoon.

A day later, Wiens, a 44-year-old Denver native, will be catching passes for his flag football team. And soon, when the snow hits, he will stop riding altogether until spring. Instead, he will ski most days, when he is not playing on his recreational league hockey team.

“I try to make fitness part of everyday life,” Wiens said. Like his wife, the Olympic bronze medalist Susan DeMattei, Wiens was a professional mountain biker until he retired from the circuit four years ago. Now he races just a few times a year to stay in shape.

“But I make it fit our family life,” he added. “That’s what’s most important to me.”

That may not be the workout regimen expected of a cyclist who two months ago pushed and broke Armstrong, the man who seemingly could never be broken in his seven consecutive Tour de France victories. Their competition, in the Leadville Trail 100 mountain bike race, set in motion Armstrong’s decision to make a professional comeback.

“I’d thought a little bit about coming back to cycling before that,” Armstrong said in a recent interview. “But the process of training for it and excitement of being on the start line and competing again went a long ways to kick-starting a comeback.”

Armstrong had officially retired from racing three years earlier, when he won that seventh Tour de France. But as someone who never fell completely out of race shape, and who had put in some serious training to prepare for the race, he did not go to Leadville on Aug. 9 to lose.

But he did.

The 100-mile race is brutal, starting at 10,200 feet, climbing at one point to 12,600 feet and covering a total of 14,000 feet of climbs.

The two men worked together for most of the race, taking turns in the lead, which put them 20 minutes ahead of the rest of the pack. In a scene they described afterward, Wiens moved aside with about 10 miles to go to let Armstrong take the lead as they headed onto an uphill trail. This time, however, Armstrong told Wiens: “No. Go. I’m done.”

Wiens, known to cheer on competitors even midrace, replied: “No. Come on.”

“Go,” Armstrong said.

“I didn’t ask him twice,” Wiens recalled recently, and he rode away from Armstrong, though not completely.

Wiens went on to break his own record, set last year, by finishing in a time of 6 hours 45 minutes 45 seconds. He has won the Leadville Trail 100 six years in a row.

Armstrong, who finished nearly two minutes behind him, said he had never in his career told another cyclist he was done during a race.

“At that stage, it’s pretty much whoever has the strongest diesel engine is going to win, and he just powered away,” Armstrong said.

It turned out to be a race with worldwide implications. Armstrong soon said he had gotten that racing itch again and intended to stage a comeback. He wants to race the Tour again — and maybe have a rematch with Wiens at Leadville — and use it as a vehicle to raise awareness for his fight against cancer. On Monday, Armstrong announced he would ride next year’s Giro d’Italia.

Armstrong beat cancer a decade ago before beginning his onslaught on the world’s most famous bike race, the Tour de France, which made him the world’s most famous cyclist, if not its most controversial, because of allegations — never proven — of his use of performance-enhancing drugs.

If Armstrong’s comeback pans out as he hopes and he is competitive, it may be remembered that his comeback began with what might now be considered one of the world’s most famous, quirky and physically daunting mountain bike races. Not only did Wiens defeat Armstrong in the Leadville, but a year earlier, he edged Floyd Landis, the disgraced former Tour winner.

Wiens remains little known in the general public — many of the headlines after the Leadville focused on Armstrong’s second-place finish — even though he did what some thought was impossible.

“Everyone in biking knew Dave before,” said Ken Chlouber, the founder and president of the Leadville Trail 100 race series, which includes other bike races and runs. “He’s a plain, down-home, nice person who happens to be an off-the-chart athlete. But now, he’s the giant killer.”

Wiens was born in a Denver suburb to Duane, a graphic designer, and Barb Wiens, a registered nurse. His parents grew up in Mennonite churches in Kansas and Idaho, but not in the mountains. Wiens was also raised in the Mennonite church, though he no longer attends.

“No, there are no mountain people in my gene pool before they moved to Denver, even though I made a career out of winning races at elevation,” Wiens said with a laugh, dismissing the speculation that he must have some altitude heritage.

Wanting to pursue his outdoor passions, Wiens went to Western State College in Gunnison in 1982, all the better to be close to great white water and ski terrain. It would take him six years, with time off here and there to try his luck at ski and kayak racing, to graduate.

In 1986, he got his first mountain bike — a 1985 Specialized Stumpjumper, one of the most popular of the first wave of commercially produced mountain bikes.

That he was already living in Gunnison, one of the two major areas for mountain bike racing — Marin County, Calif., near San Francisco, being the other — made it a natural fit.

“I started to do that and was pretty good right away,” he said. “And around here, you raced around the best guys in the sport.”

Bigger than most mountain bikers, at 6 feet 2 inches and 185 pounds, Wiens turned pro in 1988. He began a quick ascent into the fledgling world of pro mountain bike racing at a time when bicycle and bicycle component companies were starting to pour millions of dollars into the sport.

Riding first for Diamondback, the bike company, Wiens quickly became one of the top riders and began traveling the world with the team, which also happened to include his future wife. They now have three boys — Cooper, 10, and 8-year-old twins, Ben and Sam — and live in a home they built right off Gunnison’s small downtown.

Over 16 years, Wiens built a steady, if not stellar, career, winning two World Cup series races, finishing third in a World Cup final, and as recently as 2004, winning a United States Cycling National Championship in a 65-mile race.

“If you were to name a top 10 of mountain biking legends in the United States, he’d be on the list of important characters,” said Neal Rogers, the managing editor of VeloNews, the biking magazine.

That is why Wiens was inducted into the Mountain Biking Hall of Fame in Crested Butte, Colo., in 2000, three years after his wife was inducted.

Along the way, he acquired a reputation for quirky behavior: wearing the wrong color socks — “Who knew when we were starting out what was right?” he asked, still wearing gray when most riders wear white — strapping a cheap plastic watch to his handlebars as his only indication of time during races and refusing to shave his legs. His most common nickname in the field is “Wiensy.” But being one of the few racers to not shave his fair-haired legs earned him another: the Vanilla Gorilla.

Last year, after he beat Landis at Leadville, a company based in Germany that had provided him with a new handlebar grip, Ergon, signed him to be a spokesman and sometime member of its team, Topeak-Ergon.

“My goal last year was to sign an iconic mountain bike man, a guy about my age who our core consumer group could relate to,” said Jeffrey Neal, 55, the company’s vice president for United States operations. “It’s worked out better than we could have hoped. People look at that, a 44-year-old, racing like that and say ‘If he can do it, I can do it’. ”

Wiens says he is glad for the attention and hopes he inspires people, but he knows next year’s Leadville race will be even more challenging.

After a bike industry convention last month in Las Vegas, he ran into a top pro mountain biker who told him, “I was talking to my manager and saying, ‘Someone’s got to beat Wiens.”

“So, I know they’re coming,” Wiens said. “These are the guys I retired from, because I was tired of getting whupped up by them. I’m going to be a year older, but I’m not going to shy away from them. I’m going to give it a go.”

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: October 15, 2008

An article on Tuesday about David Wiens, the cyclist who recently defeated Lance Armstrong in a 100-mile mountain bike race, misidentified the state where his mother grew up. It is Idaho, not Utah.