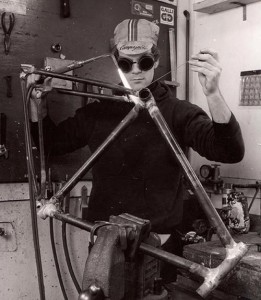

Chris Chance

This is from an article in Bike Magazine in June 1994 written by Ted Costantino.

Here on the worn-out East Coast, where everything has a history, the big book of mountain bikes starts with Chris Chance. Even as the first fat tires began roaming the Berkshires, Adirondacks and Appalachians, Fat Chances, as Chance’s bikes were dubbed, were our secret weapon. They went where no other bikes could go.They climbed hills no other bike could clean, and they snaked along trails with nary a tread misplaced.

In fact, when Chris built his first fat Chance in the summer of 1982, there was, quite literally, nothing else like it. West Coast bikes from Tom Ritchey and Gary Fisher had ultra-long chainstays, shallow head angles and low bottom brackets. Even production bikes were weird:The first Stumpjumper stays yawned about 19 inches over the horizon. But Fat Chances were different, with buzz-cut chainstays, upright angles, and high bottom brackets to clear the stumps, boulders and eruptions common to New Englands battered terrain. In other words those Fats already looked alot like the bikes we ride today.

By 1984, most of the hip new iron rolling out of California’s fabled custom shops had distinctly Fat-like aspects. That’s no coincidence: Chance’s advanced geometry was a hot topic at Kay Peterson’s Crested Butte summit in ’83. “I remember sort of preaching the word at Pear Pass,” Chance recalls now from Fat City’s rehabbed digs in scenic Somervile, Massachesetts. “A lot of the West Coast guys were really into downhills, but their bikes didn’t climb so well. I said, “On the East Coast we like to ride uphill. And we need a bike that can go through the singletrack, too.” And they were saying,”What’s that, man?”

So why didn’t Chance’s presence at the creation in ’83 (and subsequent Crested Butte meetings since) make him a household name today? “Some of it is that East Coast versus West Coast thing” Chance muses. “We’re not from the West Coast, so we’re ignored to a cetain extent.”

And some of it, I’d wager, is that Chris and crew are so self-effacing, probably to a fault. Unless you ask for something specifically gaudy, your Fat will blend right into the woods. And unless you press Chance for details, you won’t hear about such singular frame features as the Double Chin gusser, which keeps your downtube intact, or the externally machined head tube for headset reinforcement, or the almost invisible seat-stay tab that solidifies and strengthens the seat cluster, or why every Fat ever made has untapered chainstays and why the fat-tire world is a better place for it. All are Fat City innovations and each is too difficult or too expensive for others to copy–but too valuable for Fat City to abandon.

The only place Fat City makes waves is in the names its bikes carry. Even here, though, Wicked, Yo Eddy, and Buck Shaver cause more puzzlement than prominence. For the record then: “Wicked” is a hallowed New England idiom that’s an adverb, like “totally,” and an adjective, like “amazing.” Thus it is not only possible to ride a Wicked, or even a wicked Wicked, but a wicked wicked Wicked. “Buck Shaver,” a new addition this year, is the honest-to-Pete name of a former employee and it’s also the least expensive Fat you can buy.

And “Yo Eddy”? Well, it’s, uh, something else. It defies simple exegesis, yet to those in the know, it needs none. The only way to describe it is to say it’s sort of a way of life that you’ll understand once you ride one.

Pick a Yo and you’ll also get the Yo Eddy fork, Fat City’s only patented design(there’s that modesty again), and an inspiration to a host of imitations that don’t quite work as well.

So Chris has introduced a lot of new ideas into the sport, but one patent and a host of firsts do not a high profile make. And he is, somewould say, conservative, pointing out that only this year did a full-suspension Fat (the Shock-A-Billy) emerge. And who but Chris would have declined the opportunity to build the world’s first titanium mountain bikes? Instead he handed that plum to Gary Helfrich, a Fat City immortal who supplied one-third of the horse power that became Merlin Metalworks.

Still, that legacy, and that history, only confirm Chance’s pioneering status. That alot of fat-tire development wouldn’t have happened without him is a fact. That you may not have known it until now is understandable. That some day, somewhere, a Fat Chance or its siblings may figure in your fat-tire future is a prospect to be relished.